The popularity of true crime entertainment—from books to movies and television shows—has increased significantly in recent years. And when readers and viewers obsess about the type of work detectives, FBI agents, and criminal profilers do, they’re obsessing about the work of people like James R. Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald, who will speak about his distinguished career at the Fox School Wednesday, April 18 (3 p.m., Alter Hall, MBA Commons 7th floor), studied law enforcement and corrections at Penn State before becoming a police officer in Bensalem Township, Pennsylvania. He climbed the ranks, from patrol officer to detective to sergeant, and was then recruited by the FBI in 1987. His first assignment was to the FBI/NYPD Joint Bank Robbery Task Force. Then he was promoted to a supervisory special agent as a profiler and later a forensic linguist, a job that put to work his two master’s degrees in organizational psychology (Villanova University) and linguistics (Georgetown University).

His first case as a profiler? The Unabomber investigation, one of the longest (17 years) and most expensive criminal investigations of the 20th Century.

His work with the FBI helped put Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, behind bars. He has since written three books about his life and career, the most recent being A Journey to the Center of the Mind, Book III, which focuses on his first decade working with the FBI. He has also worked as an advisor and producer for several television shows, including CBS’s Criminal Minds and the Discovery Channel’s recent Manhunt: Unabomber.

In advance of Fitzgerald’s public event at the Fox School, we spoke to him about his exciting career path.

The work of criminal profilers has become household knowledge to many, but for those who may not know, can you explain what it is a profiler does?

“A profiler looks at the behavioral aspects of a crime or a crime scene and attempts to determine personality and demographic factors about the offender or offenders. They’re usually invisible clues, not forensic clues, and they’re based on psychological issues or issues regarding to the specific needs of the offender. Experienced profilers can determine what kind of offender it is and what he or she might do next and where they might do it.”

When you started working for the FBI in the late-1980s, profiling was still a fairly new practice. What was it like working in what was then a new, rare profession?

“Profiling came into its heyday in the 1980s and ’90s. I’m generally considered the third generation of FBI profilers. The concept of profiling was still very new and people, including the law enforcement community, were just finding out about it and learning that it wasn’t magic or mysterious, but involved an extensive knowledge of existing violent crimes, learning how and why each of those offenders committed those crimes, and the behavioral clues left behind.

“Profiling involves extensive knowledge of the criminal mind; I had been a police officer for 11 years and an FBI agent for seven years before I became a profiler. To be a good profiler, you have to have spent time at violent crime scenes interviewing victims and witnesses, and/or dealing with arrested individuals once they’re in the penal system. As a new profiler, part of my training was to go to prisons and meet with convicted lifers who’d committed violent crimes and interview them, just like in the TV series Mindhunter.”

Your first assignment as a profiler was to track down the Unabomber. This turned out to be a huge, life-changing case. How did you deal with the pressure of that situation?

“It was definitely a pressure-laden situation, especially because we knew he could bomb again at any time. He already killed three people, injured several dozen, and his bombs were getting more lethal. In June of 1995, he sent his ‘Manifesto’ to The New York Times and he wrote in accompanying letters that if they published it, he’d stop bombing for purposes of killing, but not for purposes of sabotage. A lot of people forget that last part. I believed he would try to keep his word, and I thought that by putting the ‘Manifesto’ out there someone might recognize his writing style, themes, and topics. There were debates within the FBI’s UNABOM Task Force in San Francisco whether to publish it or not; I firmly believed we should publish it and I stated so.

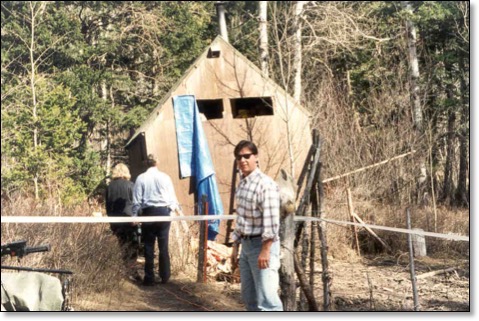

“There was so much linguistic evidence in it, and we finally got approved at the highest levels of government to publish it. The pressure was there. We knew that if we made a mistake it could possibly result in more bombings. Kaczynski, at the time, was just one of many suspects. I was the expert on the ‘Manifesto,’ then in February of 1996 I was asked to read a 23-page document that was faxed to me back at the FBI Academy in Quantico. It turned out someone named David Kaczynski, Ted’s younger brother, through his attorney, had turned over this document to the FBI. I read it, compared it to the ‘Manifesto,’ and told the UTF bosses either it was an elaborate plagiarism or ‘you’ve got your man.’ The latter was eventually proven to be correct. I went back out to the UTF in San Francisco, and about eight weeks later, the Unabomber was arrested and he never saw the light of day again.”

Your career has evolved in such a unique way, especially now that you’re writing books and working on television shows. How have you stayed open to these new career pathways?

“Life is full of adaptation. As an undergrad or grad student, you have to be willing to veer left or veer right, and sometimes even go backwards, to achieve your goals. Everyone’s life is a journey. My life varied over the years with different types of assignments within my profession. As a Bensalem police officer, I remember sitting on top of a billboard on I-95 looking for guys stealing cars. Throughout my career, I did undercover drug buys, responded to the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993, and had my first job as a profiler be the Unabomber case. The language analysis work I did on that case set legal precedent on how language can be used in the courts. Now I’m having a second life in Hollywood. I’ve adapted from street officer to FBI special agent to profiler to forensic linguist to TV consultant and writer. And I don’t think I’m done adapting yet. I remain open and excited to see where it takes me next.”

This event, sponsored by the Department of Legal Studies in Business, is part of an ongoing series of celebrations commemorating the Fox School’s 100th anniversary.

Learn more about the Fox School’s Department of Legal Studies in Business.

For more stories and news, follow the Fox School on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.