A closer look at mortgage lending behavior shows that banks with higher environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores are lending less money to low-income communities.

The notion that corporations have an obligation to prioritize social responsibility–sometimes at the expense of profits–seemed unreasonable as recently as 30 years ago. As the idea has gained popularity in the field of economics in recent decades, the number of corporations making claims about their environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance has exploded.

ESG measures, in a single number, how well a corporation addresses a number of varied issues, including their environmental impact, racial and gender inclusion, management structure and more. But do ESG scores truly correlate with corporate responsibility? According to Wei Wang, professor of accounting at the Fox School of Business, the answer is yes–just not in the way you might expect.

Wang and Sudipta Basu, a Robert Livingston Johnson Senior Research Fellow, ask whether companies boasting high ESG scores truly embody corporate responsibility in their actions. Their paper, Walking the Walk? Bank ESG Disclosures and Home Mortgage Lending, studies the correlation between ESG scores of commercial banks and their home mortgage lending practices to low-income communities.

The results are surprising.

“A lot of people would come into the story thinking that if the bank is supposedly altruistic and ESG-centric, they probably ought to do more lending in low-income areas because that is where people are in most dire need of funding to buy houses,” Wang says. “But we find the opposite. High ESG rating banks, compared to low ESG rating banks, actually cut lending more when it comes to low-income areas.”

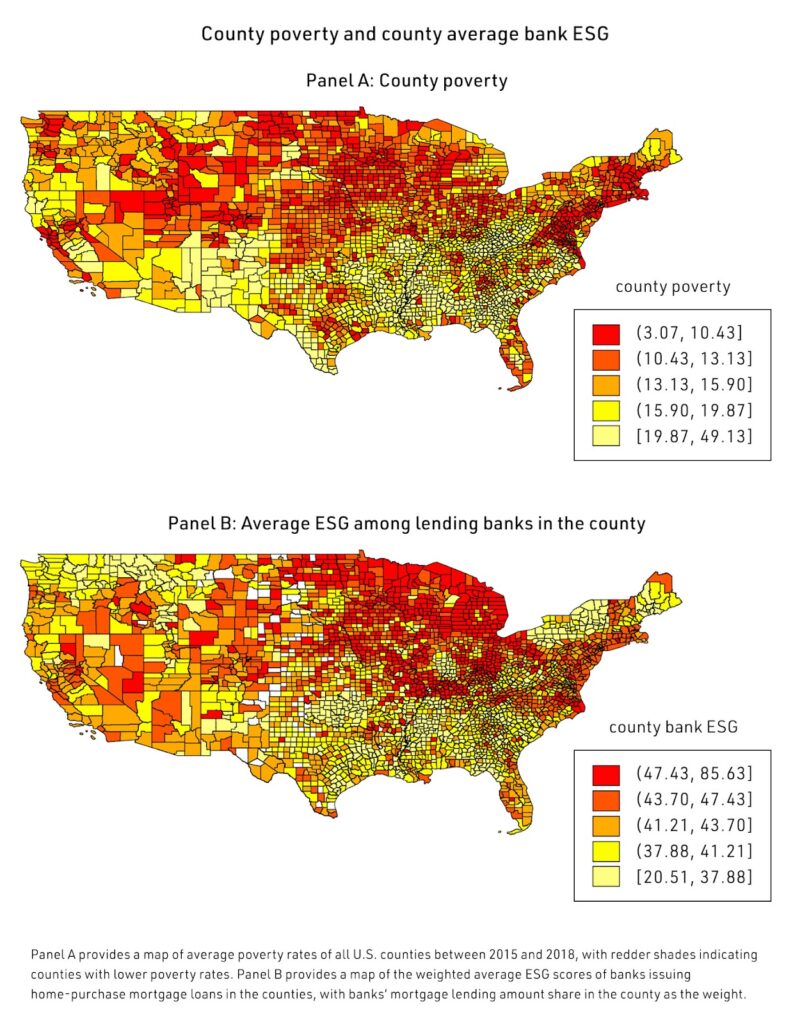

The figure below compares a map of poverty levels with a map of average ESG scores of home mortgage lenders. In the top figure, the red indicates areas of lower rates of poverty. In the bottom figure, the red indicates counties with higher average bank ESG scores.

The mirror image of the two maps reflects the finding that banks with higher ESG scores grant fewer home mortgage loans in low-income areas. This holds true at the census tract level as well.

Why would banks with high ESG scores not be lending equitably?

Wang and other academics coined the term “social wash” to describe this dynamic. Social wash describes when banks use socially conscious rhetoric and symbolic actions while not lending much to disadvantaged communities.

“Banks engage in social wash because the benefits of talking about their ESG behavior are many, but the costs are very low,” Wang says. “Even if you engage in social wash, you rarely get caught. And even if you get caught, there is no punishment.”

The motivation for social washing is clear. But given that all banks have these incentives, why is there such a direct relationship between a bank’s ESG and home mortgage lending practices?

More than anything, ESG scores may be a reflection of a bank’s profits. Banks with more resources can afford to take targeted actions that boost their ESG scores, such as hosting charitable events, investing in green energy and improving the racial and gender diversity of their board. While positive, these actions do not tell the full story of high-resource banks.

“There are all these things they can do that are good,” Wang says. “But when it comes to the stuff that matters the most in terms of boosting society’s value, there is a discrepancy between disclosures and their actions.”

Meanwhile, smaller banks with fewer resources cannot invest as much into their ESG score. Despite that, Wang finds that in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, it was the smaller, lower-ESG banks that lent more generously to communities left in disarray.

Wang is careful to note that neither he, Basu nor the paper, is taking a stance on whether it is indeed banks’ obligations to lend to low-income communities. According to traditional economic theory, there is a strong case to be made that this is a risky investment.

“ESG is asking if companies can do good to the environment and to society, in addition to making profits,” Wang says. “That is a lot to ask of companies.”

Regardless, the findings convincingly indicate that ESG scores are less than accurate indicators of equitable lending practices. For anyone that is seeking to identify responsible banks–whether it be investors, individual consumers, or policymakers–it would be unwise to take ESG at face value.

More broadly, the findings point to an ethical issue of companies using public relations messages that do not reflect their actions. Many advocates, including former Fox faculty Sherry L. Williams, are working to help restore trust between banks and communities that have been excluded from mainstream financial institutions. The deception of ESG scores undermines this work by misleading stakeholders about which banks to support.